[1] Hibiki is a Japanese whisky.

[2] Franquelo, Manuel, conversation with the author, Madrid, 27 January, 2017.

[3] Franquelo, Manuel, an email to the author, Madrid, 4 February, 2017.

[4] Oulipo was a group of writers, thinkers and mathematicians founded in 1960 by Raymond Queneau and François Le Lionnais. Duchamp was a member. Its most famous novelists were Italo Calvino and Georges Perec.

[5] Perec, Georges, The Void, Harvill Press/Harper Collins, New York, 1994

[6] Franquelo explains further: 'I have in mind an audience that belongs to a culture (world view if you like) similar to mine.' Franquelo, Manuel, email to the author, Madrid, 7 February, 2017

-

The Photography Show, AIPAD 2022

Center415 • Stand 222 20 - 22 May 2022After what seems like an eternity, we are so looking forward to once again being in New York for The Photography Show presented by AIPAD. To be amongst you, our...Read more -

ART GENÈVE 2019

Palexpo • BOOTH B39 31 Jan - 3 Feb 2019A preview of what Michael Hoppen Gallery will be taking toArt Geneva, SwitzerlandRead more -

Aipad 2018

New York • Booth 206 5 - 8 Apr 2018Michael Hoppen Gallery will be exhibiting upcoming artists alongside acknowledged 20th and 21st century masters.Read more

-

PARIS PHOTO 2017

Grand Palais • Booth C10 9 - 12 Nov 2017Michael Hoppen Gallery will be at Paris Photo, 2017, booth C10.Read more -

AIPAD 2017

Booth 512 30 Mar - 2 Apr 2017An assortment of works from the collection that MHG will be taking to this years Aipad art fair in New York.Read more -

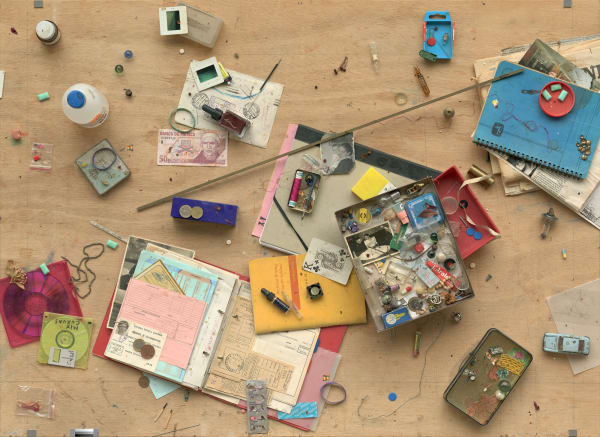

Manuel Franquelo

Things in a Room 7 Mar - 3 May 2017The Michael Hoppen Gallery is pleased to announce the Spanish artist Manuel Franquelo’s first solo show in the United Kingdom.Read more -

PARIS PHOTO 2016

GRAND PALAIS • Booth C10 10 - 13 Nov 2016Michael Hoppen Gallery will be showing at this years Paris Photo. Bringing an exquisite selection of rare and beautiful photographic prints.Read more

-

The Photography Show Presented by AIPAD 2022

MICHAEL HOPPEN'S HIGHLIGHTS April 29, 2022After what seems like an eternity, we are so looking forward to once again being in New York for The Photography Show presented by AIPAD!...Read more -

Manuel Franquelo | Actual Size!

'Photography at Life Scale' at the International Center of Photography January 28, 2022How big can a photograph be? From postcards to giant billboards, they are almost any dimension, but what happens when they are the very same...Read more -

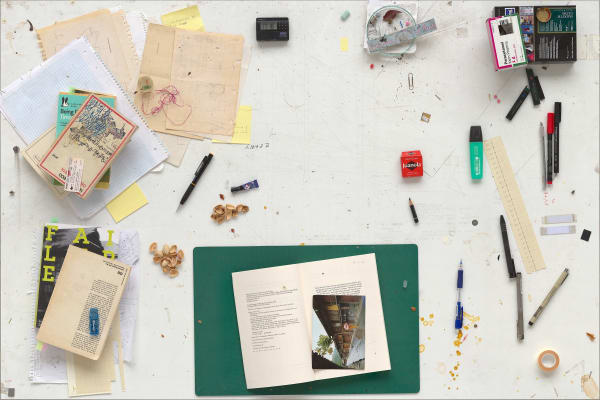

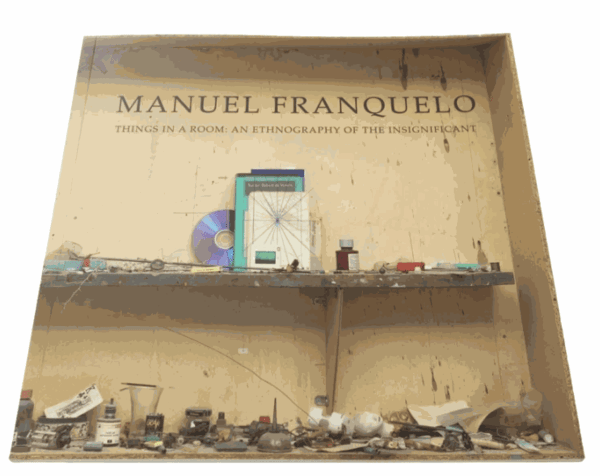

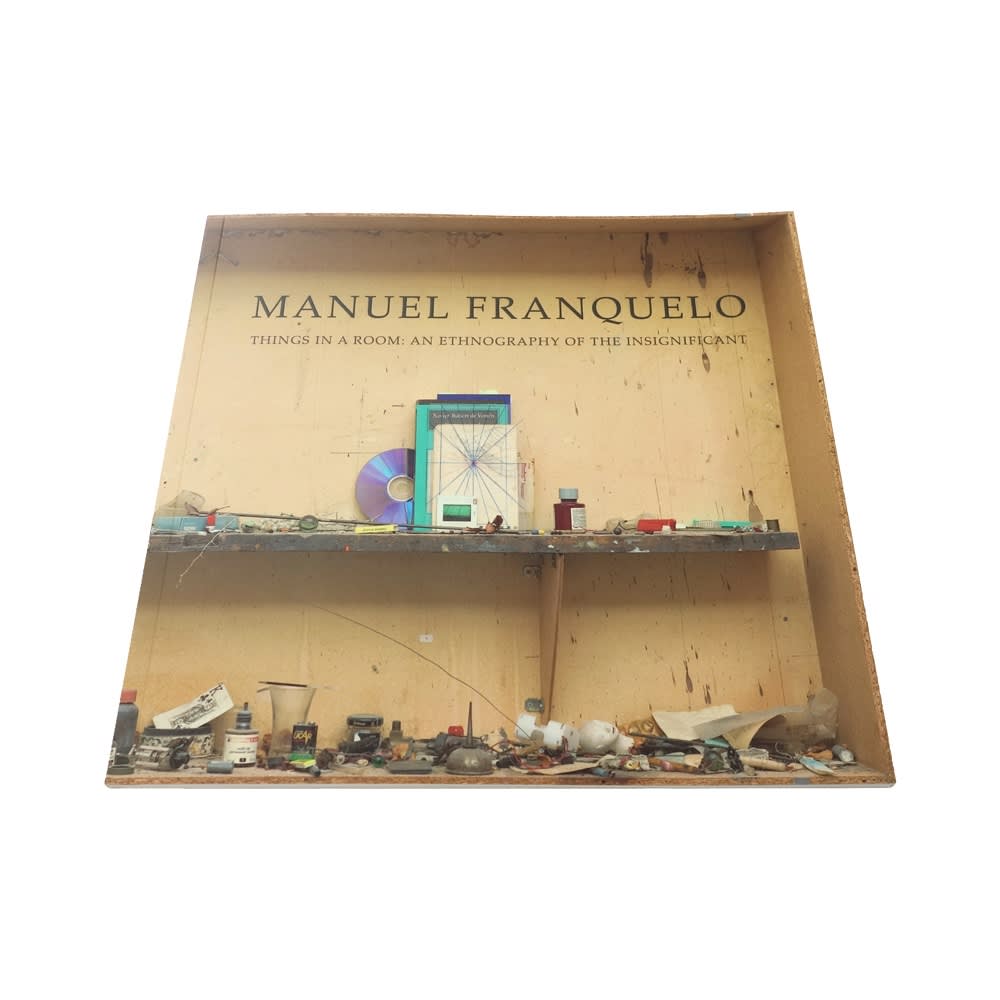

MANUEL FRANQUELO

Limited edition Exhibition Catalogue March 2, 2017A limited edition exhibition catalogue for Manuel Franquelo's 'Things in a Room' is now available to buy online.Read more

-

The Hyperreal Photographs That Must Be Seen to Be Believed

Hannah Tindle, AnOther Magazine, March 21, 2017 -

Manuel Franquelo, Things in a room: an ethnography of the insignificant

L'OEIL DE LA PHOTOGRAPHIE, March 16, 2017 -

Things in a Room: Manuel Franquelo documents objects he's collected over three decades

Katy Cowan, Creative Boom, March 16, 2017 -

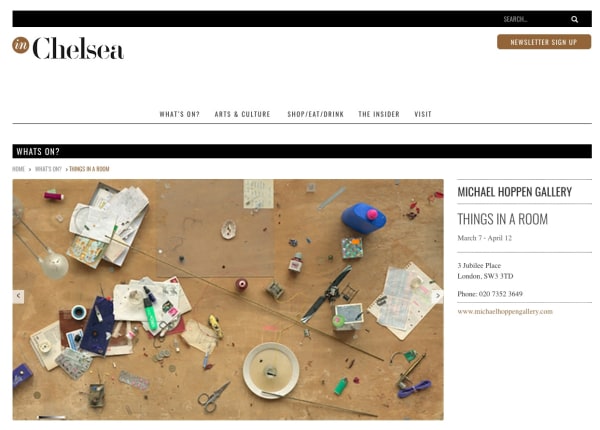

Whats on

In Chelsea, March 14, 2017 -

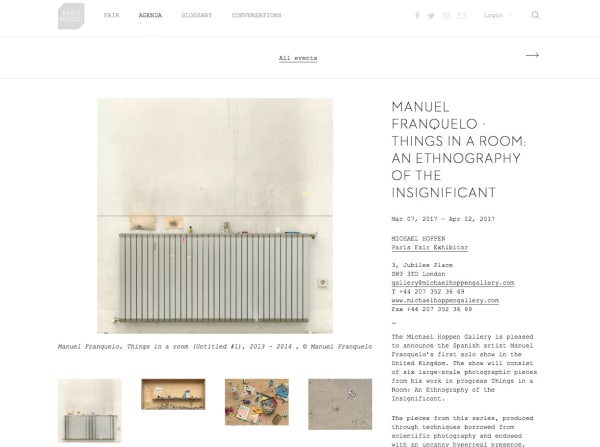

Manuel Franquelo - Things in a Room: An Ethnography of the Insignificant

PARIS PHOTO online, March 8, 2017 -

EXHIBITIONS TO SEE IN MARCH: MANUEL FRANQUELO THINGS IN A ROOM AT MICHAEL HOPPEN GALLERY

REBECCA WALLERSTEINER, Luxury London, March 6, 2017 -

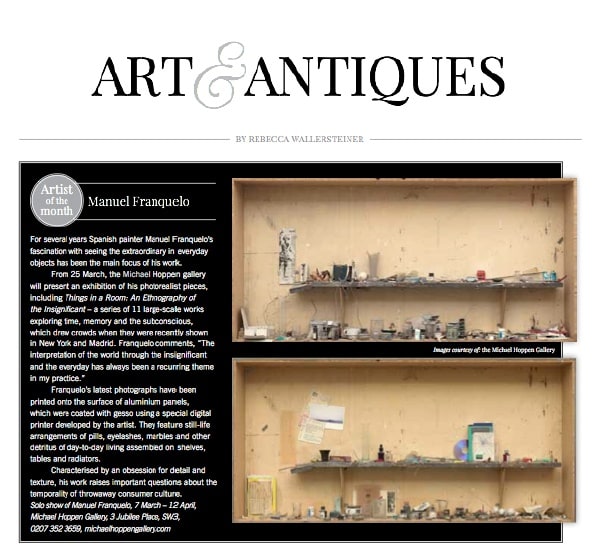

Artist of the Month

Rebecca Wallersteiner, Art & Antiques, February 16, 2017