It's a crime to take photographs this good: Early photographs by Weegee

Always in the right place at the right time, Weegee's lense was perpetually aimed the visceral and sometimes violent city of New York. In 1993, Wilma Fellig Weegee's widow, bequeathed his entire archive of original prints to the ICP in New York, and we are delighted to offer selected pieces of this unique photographers work which includes many images never previously seen in the UK.

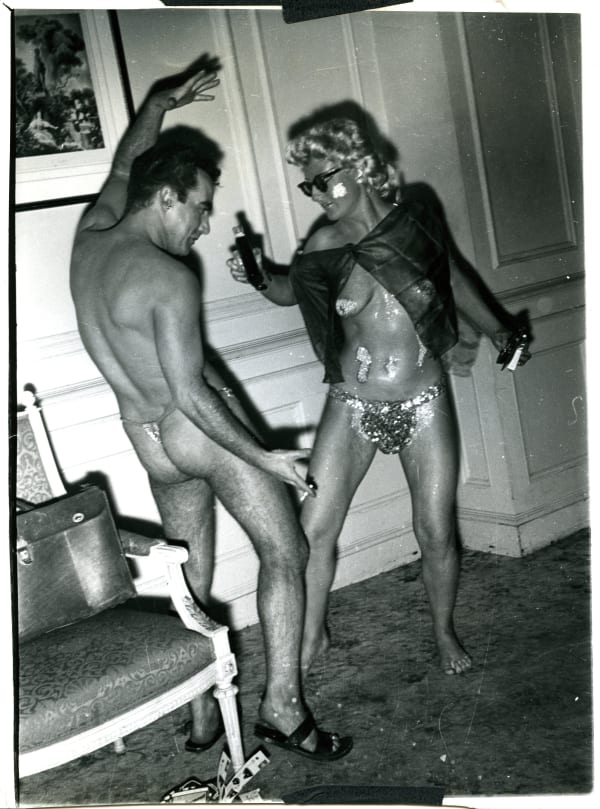

Weegee photographed New York in the 1930s and 1940s in the same iconic and instantly recognisable way Woody Allen was to film the city in the 1970s. Weegee's voyeuristic eye sought out the harsh realities of the urban experience, but also the joie de vivre and carefree attitude which typified the years between the wars.

Born in 1899 in the Austrian province of Galicia, which is today part of Ukraine, Weegee (real name Usher, then Arthur Fellig) was the second of seven children from Jewish parents. Weegee's family left Europe in 1910 for the Lower East Side of Manhattan, where Weegee grew up. He left home at 15 and in 1917 got a job in a photo studio and became assistant to a cameraman. In 1921, he got a part-time position at the New York Times and its legendary agency Wide World Photos, soon afterwards switching to Acme News pictures. Eventually, frustrated with the lack of recognition for his work, and not having his name on photographs, he became a freelance news photographer by late 1935.

Weegee's images bridge the gap between art, evidence and photojournalism. His nickname was a phonetic rendering of ouija, as in ouija board due to his sixth sense of being able to arrive at a scene minutes after the occurrence of a crime. In 1938, Fellig was the only New York newspaper reporter with a permit to have a portable police-band shortwave radio. The boot of his car was a carefully maintained darkroom, to enable him to deliver his freelance images to the newspapers as speedily as possible. He worked predominantly at night listening closely to radio broadcasts, often beating the NYPD to the scene. It also meant he was on hand to document the raucous night life in the Bowery, Harlem and The Village, and he went on to document the society events and functions of the era.

His photographs were taken with the very basic press photographer equipment, a Graflek and blue blue flashbulbs which gave his work such graphic qualities. He had no formal photographic training being entirely self taught, and was a relentless self-promoter.